How Alex Tizon profiles his subject in "My Family's Slave"

He gives us a range of her emotions, hence revealing her personality and spirit.

After four years, I’ll finally be retiring my blog catchinglight.org. The articles I’ve published there will be moved here. This is one of them.

Originally published on July 21, 2017

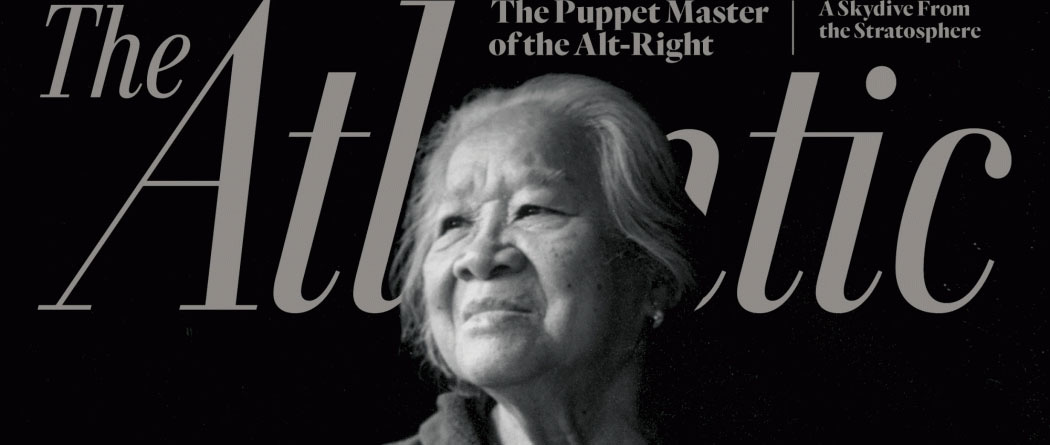

Alex Tizon’s “My Family’s Slave,” published as the Atlantic’s cover story for its June 2017 issue, finds the Pulitzer prize-winning journalist not only confessing his family’s secret and recounting his experience living with a slave. He also profiles her—Eudocia Tomas Pulido, whom he calls Lola (“grandmother” in Filipino).

How does one profile an individual who did not have agency? How does one bring out the person in someone who was dehumanized and objectified practically all her life?

In the essay, Tizon weaves two narratives together. In the first narrative, Tizon journeys from the U.S. to Lola’s hometown with her ashes. The second narrative tells of how he and his family lived with a slave in America. Essays, as a dialogue with the self on a topic, require an event that triggers interrogation or self-reflection, which manifests in the writing. In Tizon’s elegiac piece, the first event calls for the second, in that the death of Lola and bringing her remains to be buried in her province get him thinking about how she had been thrown to the life she had and who she was. For us readers, this device or style invites us to care about what is occupying the writer or speaker.

Tizon outlines Lola’s roots to give her history, if you will. We learn that she lived in Mayantoc in Tarlac province. It’s “rice country,” and Tizon saw farmers harvesting rice “the same way they had for thousands of years.” He describes the landscape as beautiful—not the “travel-brochure” kind, but “real and alive and, compared with the city, elegantly sparse.” A silhouette of Mount Pinatubo breaks the horizon. We learn that Lola and Tizon’s relatives lived in the same province, that Lola lived in a village just down the road from the property of Tizon’s grandfather.

These biographical details allow us to glimpse the life Lola must have had before she became a slave. They remind us that she had a childhood like the rest of us did, although she spent hers working the rice fields. We can imagine her move through endless fields of green to plant or harvest rice, play, wander aimlessly, or to run away. Rural life breathes a slow pace; it has its difficulties set up by poverty. “Her parents wanted her to marry a pig farmer twice her age, and she was desperately unhappy but had nowhere to go.” Tizon writes that his grandfather “saw” Lola, noticed that she “was penniless, unschooled, and likely to be malleable.” Hence the grandfather “approached her with an offer.”

Through the biographical details, we can imagine, too, the life Lola could have had if she had stayed in Mayantoc and married instead, like her siblings did. Tizon has mused about this as well and has resolved, “Maybe her life would have been better…but maybe it would have been worse.” Knowing what was taken from her—her home, her family, her freedom, the chance to find love and be married, a country—and the optional thinking of how things—and how she—could have been like had other choices been made help us mull over the gravity of Lola’s loss.

Characters or people are active or passive. In any case, to characterize them, one must show how they act and react to events: what they cause to happen or what befalls them, and how they face these.

Tizon’s second narrative holds the meat of Lola’s story, and here we get to know her as a victim and more importantly, as a person. By accounting specific details and scenes, Tizon brings his subject to our mind’s eye and we relive his past with him.

By giving us details and scenes that contain the contrasting reactions of his subject and the contrast between our expectation of Lola’s response and how she actually responds, he gives us a range of her emotions, in the process revealing her personality and spirit.

There are three very striking contrasts in “My Family’s Slave.” One of the most striking contrasts of Lola is her sound: her wail vis-à-vis her silence. As a slave, Lola toiled daily, wasn’t paid, ate scraps and leftovers on her own, slept among piles of laundry. She was beaten and lashed with insults. She wailed—“an animal cry”—when Dad punched her below the shoulder. She cried when Tizon’s parents teamed up against her, and when Mom talked to her in private.

But in the other times Lola was struck, she was silent. Her first beating was owing to Mom, who at 12 years old passed her punishment for lying about a boy to Lola. Tizon evokes his grandfather’s harsh lashing in his writing, and the unbelievable reaction of Lola:

Lola looked at Mom pleadingly, then without a word walked to the dining table and held on to the edge. Tom raised the belt and delivered 12 lashes, punctuating each one with a word. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. Lola made no sound.

Lola’s stone silence introduces us to an immensity in her—one of strength, tolerance, lowliness, acceptance. It’s a complex silence, one infused with her victimhood and fighting spirit.

This immensity also shows in the way Lola uttered Ivan’s name when Mom has had enough of him—how in one word, she muted him.

The second contrast Tizon offers is one between what he felt (and what we feel) toward Mom and how Lola treats her. Lola extended her heart even to Mom in spite of everything. She not only cooked Mom’s favorite meals, she complained about Dad with Mom, laughed wickedly with Mom, and was infuriated by Dad’s wrongdoings. Lola cooed to Mom when Mom was at her most vulnerable—cooed to Mom the way she did to Tizon and his siblings when they were young. Lola did not have to do any of those; she could have just held Mom and not said a word of comfort, but she didn’t.

One would have expected her to close herself off completely, and we would have understood her if she had. But Lola found it in herself to be affectionate, tender. She chewed Tizon’s food for him once, when he was sick—she didn’t have to do this but she did. She cooked Billy’s favorite Filipino dish whenever he slept over—she didn’t have to do this either, yet she did. Tizon pens, “I could tell by what she served whether she was merely feeding us or saying she loved us.” She attended Tizon’s daughters’ school performances and sat on the front row. She listened to them tell stories and cooked food for them too.

The third contrast is between how years of slavery could have turned Lola downcast and her being positive instead. After having a good notion of Lola’s suffering, we expect her to be at least bitter or to feel sorry for herself about her fate. Yet she showed no bitterness or self-pity; she did not let resentment consume her. We see this in the way Lola responded to Mom’s version of her first beating: Lola “looked at [Tizon] with sadness and said simply, ‘Yes. It was like that.’” No side remarks whatsoever, even if Lola was mad at Mom for her cruelty, even if she was already free to express herself. When Lola became a free woman, with her determination and initiative she learned to read and write on her own by sounding letters, doing word puzzles, watching the news and cross-checking the words she heard with the newspaper. She had hoped to read one day, and she achieved it.

To veer away from romanticizing her and to make her appear more human, Tizon recounts her quirks, what to him are Lola’s annoying habits, and mundane things. We learn that Lola panicked in the face of automation: telephones, cars, ATMs. She nagged about Dad and Ivan, nagged a 40-year-old Tizon to wear a sweater to avoid catching a cold. She kept garbage, reused paper towels. She gardened; she loved to cook. She slept hugging a large pillow. When she was young, she was so lonely she cried. In her girlhood she liked a boy named Pedro.

Tizon’s point of view is essential in his essay. It creates a sense of urgency in us, as it insists to ask what one could and would do if one’s parents had a slave, and it holds us in suspense whenever a young Tizon feebly defended Lola from ruthless Mom.

Also, thanks to his keen observation of Lola and his latch to the smallest, most intimate details, it lets us watch Lola and lets her person unfold before us.

Little by little discovering Lola’s sufferings, her desires, her fierceness, and that she is bursting with potential makes the reading experience heartbreaking, poignant, stirring, and awe-inspiring. The title alone tips us that the work is about a victim and someone who did not have agency for most of her life. Yet throughout the piece Tizon helps us see Lola through it all and witness her overcome her misfortune and hardship. This is the best thing one can do for an unsung subject.